What did forecasters get right and wrong in the largest existential risk forecasting tournament?

The first tranche of questions from our 2022 forecasting study has now resolved. Here’s what we found out.

In 2022, the Existential Risk Persuasion Tournament (XPT) brought together 169 domain experts and superforecasters to gather predictions on a range of short-, medium-, and long-run questions related to threats facing humanity, including risks from artificial intelligence, climate change, nuclear war, and pandemics. We wanted to understand whether people with opposing views could persuade each other to change their forecasts and find out if there is a link between short-term forecasting accuracy and long-term forecasts, such as predictions of existential risk.

We now have known outcomes for 38 out of the 172 questions included in the XPT. These ‘resolved’ questions asked participants to make short-term forecasts about bioweapons, renewable energy, carbon capture, nuclear weapons, AI benchmarks and other AI progress indicators. The resolved questions provide us with a unique opportunity to evaluate forecasting accuracy across expertise groups, identify key surprises, and explore the relationship between short-term forecasting skill and assessments of long-term risks.

Our latest report—Assessing Near-Term Accuracy in the Existential Risk Persuasion Tournament—analyzes the forecasts for those 38 resolved questions. In this post, we’ll briefly discuss the key findings from the paper. The full report provides more detail on these findings.

Main insights across subject areas

Respondents underestimated AI progress, especially superforecasters

Large language models achieved significantly higher scores than anticipated on the MATH, MMLU, and QuALITY benchmarks. Domain experts assigned probabilities 21.4%, 25%, and 43.5% to the achieved outcomes. Superforecasters were more pessimistic: they assigned probabilities of just 9.3%, 7.2%, and 20.1% respectively.

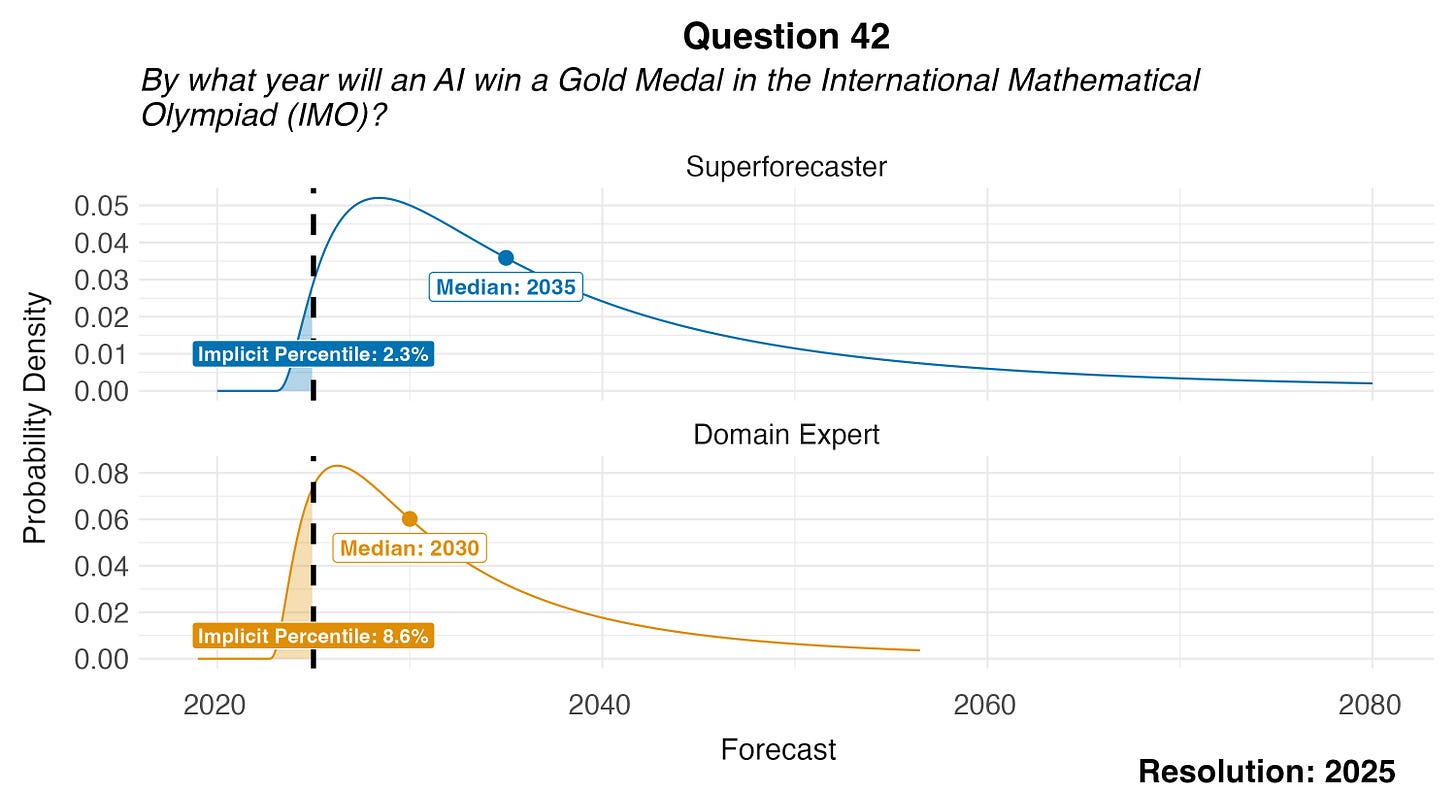

The results from the International Mathematical Olympiad were even more surprising: AI systems achieved gold-level performance in July 2025, an outcome to which superforecasters gave only 2.3% probability and domain experts 8.6%. Overall, superforecasters assigned an average probability of just 9.7% to the observed AI progress outcomes across these four benchmarks, compared to 24.6% from domain experts.

Figure 1: Superforecaster and domain expert forecasts of the year in which AI will win a gold medal in the International Mathematical Olympiad

Climate technology progress was overestimated

Forecasters were overly optimistic about the development of green technology. The cost of hydrogen produced using renewable electricity remained higher than anticipated ($7.50/kg in 2024 vs. median forecasts of $4.50/kg by superforecasters and $3.50/kg by domain experts), and direct air CO₂ capture technology captured only 0.01 MtCO₂/year in 2024 (compared to median forecasts of 0.32 by superforecasters and 0.60 MtCO₂/year by domain experts).

Key findings on accuracy

Superforecasters and domain experts had similar accuracy on short-run questions

Superforecasters and experts forecasting on questions within their domain of expertise had nearly identical accuracy scores. The performance gap between the most and least accurate XPT participant groups spanned just 0.18 standard deviations, comparable to the difference between median and slightly above-average performance. These differences were not statistically significant.

Individual forecasters outperformed public participants, but not simple algorithms

Superforecasters and domain experts both outperformed our sample of educated public participants, who scored 1.82 standard deviations below the median XPT participants—a gap equivalent to the difference between the 50th and 3rd percentile performance. Individual forecasters failed to beat two simple algorithms: a “no-change” algorithm and an algorithm that simply extrapolated the current trend. These simple algorithms performed well partly because many questions involved low-probability events (which did not occur) or slow-moving variables (where trends persisted).

Aggregate forecasts demonstrated the wisdom of the crowds

Median aggregation of XPT participants’ forecasts achieved a substantial improvement over individual performance, increasing accuracy by roughly 1 standard deviation. These aggregated forecasts show weak but positive evidence of outperforming the “no-change” forecast, though not trend extrapolation. This finding reinforces the well-established principle that combining multiple forecasts improves accuracy.

Implications for Long-Term Risks

No correlation between short-run accuracy and existential risk beliefs

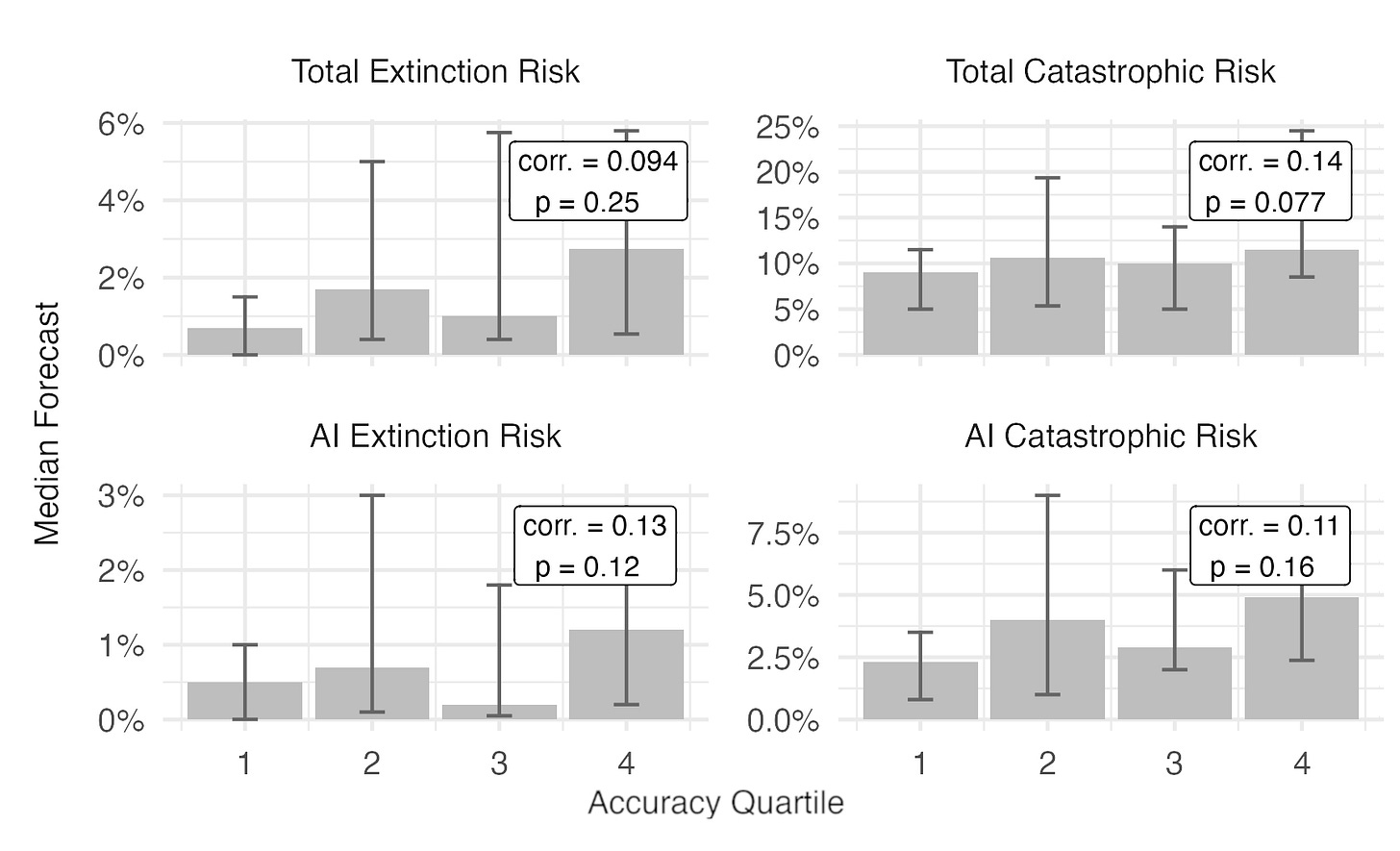

Ideally, we would use short-term forecasting ability to assess the reliability of judgments about humanity's long-term future. Unfortunately, in our XPT data, short-term forecasting accuracy did not consistently align with any particular position on long-term risks. As shown in the figure below, the correlation coefficients between short-run accuracy and various long-term risks were all close to zero, and none of them were statistically significant. Overall, our findings suggest that short-term forecasting accuracy provides limited evidence about whose longer-term risk assessments are most credible so far.

Figure 2: XPT participants’ views on risk by 2100. Participants are divided into quartiles based on their short-run accuracy scores from least (1) to most (4) accurate. Error bars represent 95% bootstrap confidence intervals for the median risk estimate within each quartile.

Looking forward to 2030

The next wave of XPT questions will resolve in 2030. These will offer deeper insights into the following:

AI development and impact. Given the faster-than-expected progress on AI benchmarks, we are interested to track how this acceleration continues in the coming years. Question #51 asks whether Nick Bostrom affirms the existence of AGI by 2030, where superforecasters estimated just a 1% probability compared to domain experts’ 9%. Other key questions include the date of first publicly-known advanced AI, US computer R&D spending, labor force participation in OECD countries, and the percentage of US GDP from software and information services.

Climate trajectory and technology. Critical climate questions with 2030 resolution dates include global surface temperature change. We will also assess progress on climate technologies through questions about green hydrogen production costs, direct air carbon capture, and electricity share from solar and wind energy. These resolutions will be particularly telling given the forecasters’ overestimation of climate technology development in 2024.

Global risk assessment. While most existential risk forecasts for 2030 were very low, we will track several important risk predictions that resolve by this date. For public health emergencies, both superforecasters and domain experts predicted approximately 2 public health emergencies of international concern declarations with at least 10,000 deaths by 2030. We will also monitor forecasts about nuclear weapon use causing significant casualties.

As these and other 2030 questions resolve, they will also enable us to answer crucial meta-questions: What is the relationship between short- and medium-run forecasting accuracy? Do forecasters who excel at medium-term prediction (5-8 years) hold systematically different views on long-term existential risks?

Want to get involved with FRI’s work?

At the Forecasting Research Institute we apply the science of forecasting to society’s most critical decisions. Our previous work includes creating panels of experts and skilled forecasters to make predictions about AI progress and LLM-enabled biorisk as well as methodological innovations for improving forecasts, such as adversarial collaboration and incentivizing truthful long-run forecasts.

We have a lot more work coming soon, including a longitudinal panel of expert predictions of AI progress, a short test to identify promising forecasters, expert views on bioweapons risk, and methods for improving low-probability forecasts.

If you’d like to collaborate with FRI or are interested in funding our work, please reply to this newsletter or email info@forecastingresearch.org.